Ten Years After Dismaland: Banksy and the Amusement Park of Disenchantment

- Delphine & Romain Class

- Sep 12, 2025

- 5 min read

In 2015, Banksy made headlines with a nightmarish amusement park set up in Weston-super-Mare, a seaside town in southwest England. Ten years later, we look back at a mythical temporary exhibition that left its mark on the history of street art and reshaped the relationship between art, entertainment, and politics.

A Park Like No Other

In August 2015, the small English seaside town of Weston-super-Mare—usually known for its family beaches and fish and chips—suddenly became the epicenter of the art world. Behind anonymous fences, Banksy unveiled to the public a project kept secret until the very last moment: Dismaland, “a family theme park unsuitable for children.”

From the very entrance, the atmosphere was set. Visitors, greeted by deliberately rude security guards, had to pass through a creaking metal detector before entering a bleak and satirical universe. At its center stood a ruined castle, a broken-down replica of Disneyland’s iconic landmark. All around, some fifty monumental works and installations created by 58 international artists—handpicked by Banksy himself—were on display.

From the very start, Banksy staged discomfort: a theme park that doesn’t welcome but instead pushes visitors away. In front of a gray fence topped with the crookedly lit sign Dismaland, people queued in the rain. Security guards with stern expressions rummaged through their bags. “It was like a Disneyland gone wrong,” recalls Laura Bennett, a local guide. “Nothing was designed to reassure—everything was built to provoke unease.”

Shocking Works for a Society in Crisis

The exhibition led visitors through a series of dystopian visions.

Cinderella Crashed:A life-sized installation showed the princess lying inside her overturned carriage, assaulted by the flashes of paparazzi capturing her fall. Banksy twisted the fairy tale to denounce the morbid media fascination with tragedy and death.

The Migrant Pond:A dark pool filled with overloaded miniature boats carrying tiny figurines, mirroring the refugee crisis in the Mediterranean. A cruel toy version of a real tragedy, it reflected the spectators’ indifference.

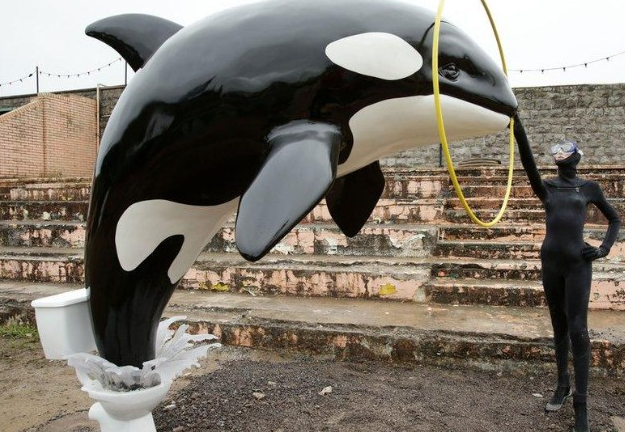

Absurd Rides:A broken-down carousel (later becoming one of the artist’s most iconic works), a fountain of black water, and a shooting gallery where visitors aimed at effigies of Mickey Mouse and Ronald McDonald. One ride turned slowly: children played on plastic horses while a butcher figurine handled hanging carcasses nearby. Beneath the innocence of play, Banksy exposed the hidden horrors of consumer society.

The Castle:At the center of the park stood a decayed, blackened replica of Disney’s castle. Its crumbling turrets and cracked walls starkly contrasted with the idealized imagery of fairy tales.

Damien Hirst’s Installation:A glass tank holding a suspended plastic shark, parodying his famous The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living. Invited by Banksy, Hirst mocked his own work, amplifying the satire.

Jenny Holzer’s Illuminated Messages:Ironical maxims in glowing red LED letters covered the walls: “PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT” and “MONEY CREATES TASTE.” Holzer’s biting slogans, seamlessly integrated into the park, reinforced its political charge.

Hostile Staff:Employees in orange vests gave curt directions with disinterest. No forced smiles here—the staff were part of the immersive experience, heightening the sense of oppression.

“You could switch from laughter to discomfort in seconds,” recalls Mark, a British visitor. “We knew we were being entertained, but at the same time, the gravity of the themes was impossible to ignore.”

Worldwide Success

In just five weeks of opening, Dismaland welcomed nearly 150,000 visitors. Tickets, sold online for £3, sold out within hours, while black-market resale prices sometimes reached ten times the original cost.

The international press widely covered the event: The Guardian called it “the perfect antidote to sanitized entertainment,” while The New York Times described it as “a lesson in contemporary politics disguised as a theme park.”

“It was the first time we’d seen an art project of this scale attract so many visitors to our town,” explained Martin Jones, a local councilor. “Everyone was talking about Weston—and not just about its pier.”

Legacy and Influence

Ten years later, Dismaland continues to spark imaginations and inspire immersive exhibitions around the world. The model of the “inverted theme park” has been adopted by many collectives and institutions.

“With Dismaland, Banksy shifted from being a street artist to a global stage director,” analyzes art historian Patrick Flanagan. “It was no longer just about a stencil on a wall, but about a complete universe where every detail contributed to the narrative.”

What Remains

The exhibition was never reproduced or reopened. After its closure, part of the structures was dismantled and sent to Calais, to be repurposed as materials for the refugee camp known as “the Jungle.” As so often in his work, Banksy transformed ephemerality into social commitment.

“What’s unique about Banksy is his ability to turn the ephemeral into a singular force,” emphasizes art critic Sarah Klein. “Dismaland no longer exists, but it still haunts the imagination of art lovers and the wider public.”

Key Figures:

Opening Dates: August 21 – September 27, 2015

Location: Weston-super-Mare, England

Duration: 5 weeks

Participating Artists: 58 (including Damien Hirst, Jenny Holzer, Jimmy Cauty)

Visitors: 150,000

Local Economic Impact: £20 million

Iconic Works:

Cinderella Crashed – a critique of celebrity culture and the media

The Migrant Pond – an allegory of the humanitarian crisis

Dystopian Carousel – a satire of consumer society

Jenny Holzer’s Illuminated Messages – ironic slogans denouncing capitalism

Biography of Banksy

Banksy is a British street artist whose true identity remains unknown to this day. Likely born in Bristol, England, in the 1970s (some sources suggest 1973 or 1974), he emerged in the 1990s as a major figure in street art.

Banksy is believed to have begun his artistic journey within Bristol’s underground scene, influenced by punk culture and New York graffiti. Inspired by pioneers like Blek le Rat, he developed a distinctive aesthetic that combines graffiti, stencils, and political messages.

The artist is known for his systematic use of stencils, which allows him to work quickly in public spaces and bypass legal constraints. His work is marked by biting irony and a critique of social, political, and economic issues.

Recurring themes include:

War and militarism

Mass consumption and capitalism

Surveillance and social control

Inequalities and injustices

Childhood as a symbol of innocence and hope

His visual style is simple, yet his striking images convey universal messages.

Some of his most famous works include:

Girl with Balloon (The Little Girl with the Red Balloon), a symbol of hope and innocence

Flower Thrower (The Flower Thrower), a pacifist reinterpretation of revolutionary imagery

There Is Always Hope, a slogan painted in London

Murals in the West Bank, including those on the Israeli separation wall, which gained international attention

Banksy maintains an ambivalent relationship with the art market. Although his works sell for record prices, he openly criticizes the commercialization of art. In 2018, during a Sotheby’s auction, his Girl with Balloon partially self-destructed immediately after being sold, becoming Love is in the Bin. This stunt only strengthened his legend.

Beyond art, Banksy engages in activism. He has carried out interventions in refugee camps (such as in Calais in 2015) and supports various humanitarian and social causes.

Today, Banksy is considered one of the most influential contemporary artists. His ability to remain anonymous while generating global excitement is an integral part of his myth. His works question society, politics, and the role of art in public spaces.

Comments